Coffee Origins Guide

Coffee is an agricultural product with a passport. Long before roast level or brew method enters the conversation, origin is already shaping what you taste: the way the tree grows, how the cherry ripens, what the seed becomes, and the baseline palette the roaster gets to paint with.

When people talk about “terroir” in coffee, they mean the full stack of factors that make one place taste different from another: altitude, climate, soil, plant variety, farming practices, and—crucially—processing decisions made at harvest. You don’t need to memorize every region to use origin well. You just need a few reliable mental models and a way to taste with intention.

This guide gives you both: a clear picture of how origin works, plus a practical map of the major regions and what they tend to produce.

The Coffee Belt

Coffee grows in a band that wraps the globe between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn (roughly 25°N to 25°S latitude). That’s not a trivia fact—it’s a proxy for the kind of conditions coffee wants: moderate temperatures (around 60–70°F / 15–24°C), a rhythm of wet and dry seasons, and (for many specialty coffees) enough elevation to slow cherry development.

The biggest producing countries by volume include Brazil (the global leader), Vietnam (predominantly Robusta), Colombia, Indonesia, and Ethiopia. But “most produced” and “most distinctive” are not the same. Some origins are famous because of consistency and scale; others because a small area reliably produces flavors that feel almost unreal.

Coffee Species (and Why It Matters)

Most of what you drink is either Arabica or Robusta, and that split alone can explain a lot of what you’re tasting.

Arabica (the specialty baseline)

Arabica tends to show greater aromatic complexity: florals, citrus, stone fruit, berries, honey, and layered sweetness. It’s commonly grown at higher altitude (often around 2,000–6,000 ft), is more delicate in the field, and is more sensitive to disease and climate stress. In the cup, Arabica is where you usually find clarity and nuance.

Robusta (the workhorse)

Robusta is hardier and generally grown at lower elevations. It often has more bitterness, heavier earthiness, and a different kind of intensity. It’s common in instant coffee and commodity blends, and it’s also used in some espresso contexts in small amounts for crema and punch. None of this makes Robusta “bad”—it just means the flavor goals are different.

If you’re buying specialty coffee and the bag doesn’t explicitly say otherwise, you can generally assume Arabica. If you’re exploring espresso blends, especially traditional styles, you may encounter a Robusta component.

How Origin Turns Into Flavor

Origin isn’t magic; it’s biology and physics.

Altitude: density, acidity, and aromatic detail

At higher altitudes (often cited around 5,000 ft and up), coffee cherries typically ripen more slowly. Slower ripening often correlates with denser beans and more concentrated development of acids and aromatics. That’s one reason high-elevation coffees frequently taste “brighter” and more complex.

Lower altitude coffees can be wonderful too—often with more body and roundness—but they may present fewer high-tone aromatics and less sparkling acidity.

Soil and ecosystem: the baseline palette

Soil doesn’t directly “taste like chocolate,” but it influences plant health, nutrient availability, and how consistently cherries ripen. Volcanic soils (common in parts of Central America and regions of East Africa) are often associated with coffees that feel vivid and layered. Clay-heavy soils (associated with parts of Brazil) often produce coffees that read as dense, grounded, and cocoa-forward.

Climate and harvest rhythm

Coffee wants stable growth but distinct seasons. The timing of rain affects flowering, ripening, and the practicality of different processing methods. Some regions support natural drying easily because the harvest season is reliably dry; others lean washed because humidity makes slow drying risky.

And then there’s the human layer: picking standards, sorting rigor, and processing discipline. Two coffees from the same country can taste radically different based on how carefully the harvest was handled.

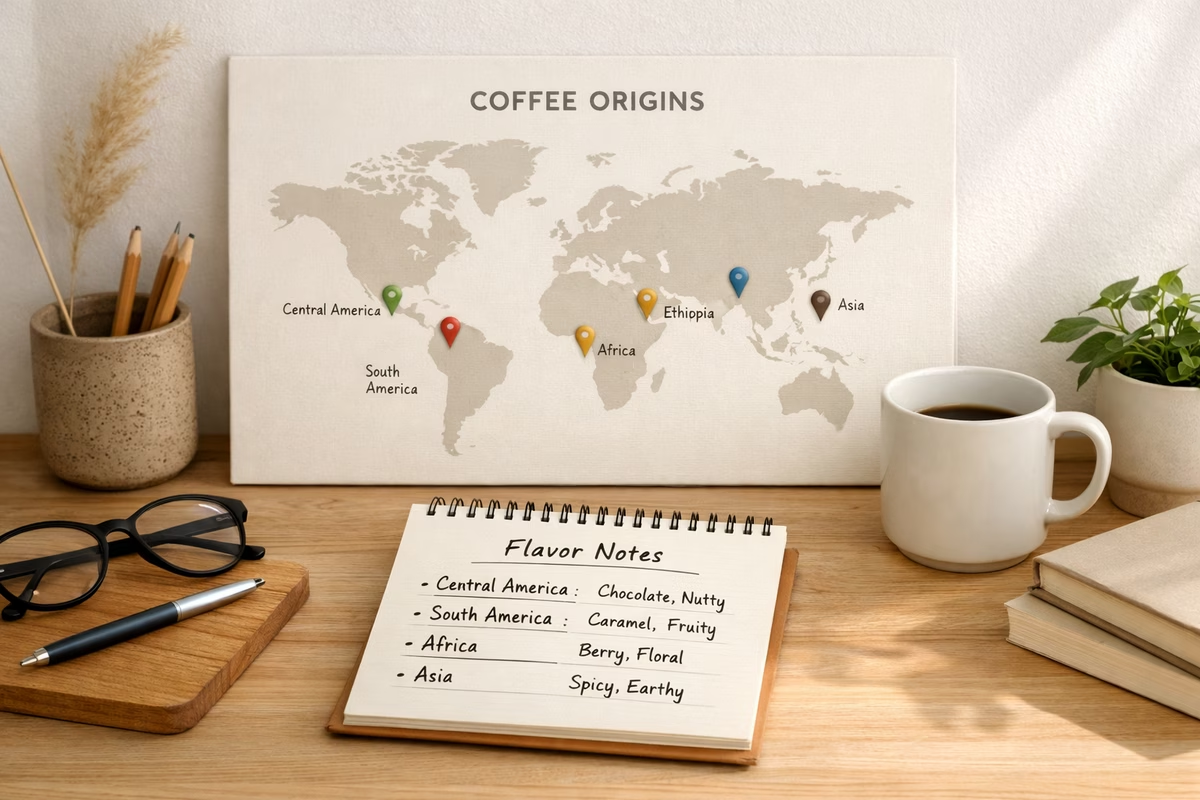

A Tasting Map of Major Origins

Think of the sections below as a map, not a rulebook. Within any origin there are microclimates, processing styles, and producer decisions that can flip the expected profile on its head. But the patterns are real enough to help you shop and taste with confidence.

Africa: aromatic, bright, and expressive

Ethiopia is often described as the birthplace of coffee, and it can taste like it: floral aromatics, tea-like structure, and fruit notes that feel closer to fresh berries or citrus than “coffee” stereotypes. Many Ethiopian coffees are processed naturally (dry process), which can amplify fruit and sweetness; washed versions often emphasize clarity and florals. Commonly cited regions include Yirgacheffe, Sidamo, and Harrar, with altitudes often around 5,500–7,200 ft. If you like jasmine, bergamot, blueberry, or a clean, tea-like finish, Ethiopia is a great place to start.

Kenya is famous for intensity and structure: bright, wine-like acidity, dark berry notes (black currant is a classic descriptor), and a juicy, complete feel. Kenyan coffees are often washed, and many people associate them with exceptional clarity. Regions such as Nyeri, Kirinyaga, and Kiambu are frequently mentioned, with altitudes around 4,900–6,800 ft. Kenya is an origin that can make pour-over taste like fruit juice—when it’s good, it’s unmistakable.

Rwanda and Tanzania often offer an accessible doorway into African profiles: bright acidity and red-fruit sweetness without always pushing the same intensity as Kenya. Rwandan coffees, including those around Lake Kivu and the Virunga Mountains (often around 4,600–6,500 ft), can be clean, sweet, and floral-fruity. Tanzanian coffees (often from Kilimanjaro/Arusha areas around 4,000–6,000 ft) can echo Kenyan structure but with a softer edge.

Central America: balance, sweetness, and polish

Central American coffees are often a “yes” for many palates: balanced acidity, caramel-like sweetness, and recognizable chocolate/nut notes—while still offering origin character.

Colombia is famous for consistency and breadth. Regions like Huila, Antioquia, and Nariño (often around 4,000–6,300 ft) produce coffees that can be medium-bodied with chocolate-caramel sweetness, nutty structure, and fruit notes that read like red apple or berries. Washed processing is common, and medium roasts often work beautifully—sweet, comfortable, and still expressive.

Guatemala is a classic choice when you want depth: richer body, cocoa tones, and spice-like accents, especially from volcanic areas such as Antigua. You’ll also see regions like Huehuetenango and Atitlán, with altitudes often around 4,000–6,500 ft. Guatemalan coffees can feel like “dessert that still has brightness.”

Costa Rica often leans crisp and clean: bright citrus, honeyed sweetness, and a refreshing finish, with regions such as Tarrazú and the Central/West Valleys (often around 3,900–5,600 ft). Costa Rica is also associated with processing innovation (including honey processes), so it’s a great origin for seeing how processing and terroir interact.

Honduras has become a strong specialty value: sweet, smooth, chocolate-caramel profiles with balanced acidity, across regions like Copán and Montecillos (often around 3,600–5,900 ft). If you want “good every day” coffee that still feels intentional, Honduras is worth exploring.

El Salvador (including areas like Apaneca-Ilamatepec and Alotepec-Metapán, often around 3,600–6,500 ft) can be creamy and sweet with brown sugar and chocolate tones and gentle acidity.

South America: scale, comfort, and espresso foundations

Brazil is the volume giant and a foundational flavor in many blends. The profile is often low-acid, nutty, chocolatey, and heavy-bodied—especially when processed naturally and roasted medium to dark. Regions like Minas Gerais, São Paulo, and Bahia are frequently cited, and altitudes can be lower than some other specialty regions (around 2,000–4,600 ft). If you like espresso that’s smooth and chocolate-forward (or you want a blend component that adds body), Brazil is a workhorse.

Peru often offers mild acidity, sweet nutty-chocolate structure, and occasional florals across regions such as Chanchamayo, Cajamarca, and Cusco (often around 3,600–6,000 ft). It’s also associated with organic production in many contexts.

Asia-Pacific: earthy depth and distinctive processing

If Africa feels like high notes and Central America feels like balance, parts of Asia-Pacific can feel like bass: earthy, herbal, syrupy, and savory—especially from Indonesia.

Indonesia (Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi) is often associated with low acidity and heavy body, with notes like dark chocolate, tobacco, cedar, and an herbal earthiness. A key driver is processing: wet-hulling (Giling Basah) is distinctive and can produce that recognizable “Sumatran” profile. Regions such as Mandheling/Gayo (Sumatra) and Toraja (Sulawesi) are frequently mentioned, with altitudes often around 2,500–5,000 ft. These coffees often take medium to dark roasts well.

Papua New Guinea (Eastern and Western Highlands, often around 4,500–6,000 ft) can surprise people: brighter acidity and a balanced, fruity-floral character that sometimes echoes Central America.

Yemen is historically important and often idiosyncratic in flavor: wine-like complexity with dried fruit (raisin/date) and spice-chocolate depth, commonly from regions like Bani Matar and Haraz. Altitudes can be very high (often cited around 6,000–8,000 ft), and availability is limited, so it can be expensive.

Hawaii (Kona) is notable as U.S.-grown specialty coffee. The cup is often smooth and mild with nutty-chocolate sweetness and low acidity. It’s also frequently expensive, and labeling matters—if you’re seeking pure Kona, look for “100% Kona” rather than blends.

Single Origin vs. Blends (How to Use Each)

Origin is easiest to learn when you taste it cleanly, but that doesn’t mean blends are “lesser.” They solve different problems.

Single origin

Single-origin coffee (one country/region/farm/lot) is your best teacher. It lets you isolate variables and notice what changes from place to place. It’s especially rewarding in filter brewing (pour-over/drip) where clarity is a feature.

Blends

Blends are designed. They aim for stability, balance, and performance—especially in espresso and milk drinks. A blend can be built around body (Brazil), brightness (East Africa), and sweetness (Central America), then adjusted through the year as harvests shift.

If you’re trying to understand origin, drink single origins. If you’re trying to make the same latte taste great every morning, a blend may be the smarter tool.

Choosing Coffee by Origin (A Practical Cheat Sheet)

If you’re standing in front of a shelf and want a fast, reliable decision, start with what you want the cup to feel like.

If you want bright, fruity, and aromatic

Start with Ethiopia or Kenya, and consider Costa Rica as a cleaner, citrus-forward bridge. Lighter roasts are often the easiest way to taste the full aromatic range.

If you want balanced sweetness with chocolate-caramel comfort

Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador are consistent choices. Medium roasts often emphasize sweetness and body without burying origin character.

If you want bold, low-acid, heavy-bodied coffee

Brazil and Indonesia are classic entry points. Roast preference matters here: medium-to-dark profiles often align with the flavor style people want from these origins.

If you want “unusual in a good way”

Try Yemen when you can find it, or look for experimental processing from origins you already like (for example, a honey-processed Costa Rica or a natural-processed Colombia). Origin gives you the canvas; processing changes the brush.

How to Read an Origin Label Like a Pro

Coffee bags often list a country, but the useful signal is in the details:

- Specificity: country → region → cooperative/farm → lot. More specificity usually correlates with a more traceable, intentional coffee.

- Altitude: not always listed, but when it is, it can hint at density and acidity potential.

- Processing: washed vs natural vs honey can shift flavor as much as origin.

- Harvest/lot info: when present, it suggests the roaster is treating the coffee as seasonal and distinct.

If the bag only says “Colombia” with no other details, that doesn’t make it bad—it just means you should expect a broader, more generalized profile.

A Simple Way to Learn Origins (Without Getting Overwhelmed)

Do a three-cup rotation for two weeks:

- One washed Central American (for baseline balance)

- One washed Kenya or washed Ethiopia (for clarity and brightness)

- One natural Brazil or wet-hulled Indonesia (for body and depth)

Keep your brew method consistent, and write down three things: aroma, acidity feel, and finish. After a handful of cups, “origin” stops being a concept and becomes a tool you can use.

Next Steps

- Processing Methods - How coffee is processed after harvest

- Roasting Guide - How roasting affects origin flavors

- Coffee Database - Browse beans by origin and flavor profile

- Sumatra

- Brazil

- India

Roast: Medium to dark

Want Sweet, Smooth Coffee?

Choose:

- Brazil

- El Salvador

- Hawaii (Kona)

Roast: Medium

Want Complex, Exotic Coffee?

Choose:

- Ethiopia (natural process)

- Yemen

- Rwanda

Roast: Light

Reading Coffee Labels

What to Look For

Country/Region: Indicates general flavor profile

Specific Region or Farm: More specific = higher quality, traceability

Altitude: Higher = better (generally)

Processing Method: Affects flavor significantly (natural, washed, honey)

Roast Date: Most important! Use within 2-4 weeks.

Variety: Bourbon, Typica, Gesha, etc. (less common but indicates quality)

Takeaway

Origin matters: Where coffee grows determines flavor as much as roast level.

Start with regions:

- Africa (bright, fruity, floral)

- Central America (balanced, chocolate, caramel)

- South America (nutty, smooth, sweet)

- Asia (earthy, bold, full-bodied)

Experiment: Try single origins from different regions to discover your preferences.

Roast matters too: Light roasts showcase origin. Dark roasts emphasize roast character over origin.

Buy fresh, traceable coffee: Look for roast dates, origin details, and quality indicators.

Next Steps

- Processing Methods - How coffee is processed after harvest

- Roasting Guide - How roasting affects origin flavors

- Coffee Database - Browse beans by origin and flavor profile