Fermentation & Flavor Design for Hot Sauce

There is a quiet magic to the jar on your counter: heat that once punched you in the nose becomes layered, round, and endlessly interesting. Fermentation is less about taming peppers and more about listening — to salt, microbes, time, and the slow alchemy that unfolds in a cool, dark place. This guide is part field notebook, part recipe, and part love letter to fermented chiles.

If you’ve only made quick vinegar sauces, fermented sauce will feel like a new ingredient rather than a new recipe. The difference is depth: fermentation adds acidity that tastes “alive,” sweetness that feels integrated, and savory notes that can make even a simple pepper blend taste composed.

We’ll focus on two things at once:

First: making safe, predictable ferments (the jar behaves, the flavor improves). Second: designing flavor on purpose (your sauce has a clear personality).

The Promise of Fermentation

Fresh chiles can taste bright, vegetal, and sharp. Fermentation takes those raw notes and translates them: lactic acid adds plush acidity, ester compounds lend floral and fruity hints, and the overall impression shifts from aggressive heat to savory complexity. The result can be an umami-rich sauce with length, nuance, and surprising sweetness.

The Palette: Choosing Your Peppers

Think of peppers like paint. Their raw character will inform the ferment’s personality.

High-heat peppers (habanero, scotch bonnet, bhut jolokia) can produce floral, tropical aromatics when fermented—perfect when you want perfume beneath the heat. Mid-heat peppers (serrano, jalapeño, fresno) give you peppery brightness and a forgiving backbone. Mild peppers (pasilla, ancho, poblano) add depth and body without stealing the spotlight. Smoked or dried chiles (chipotle, guajillo) should be used sparingly; smoke persists through fermentation.

Blending peppers lets you sculpt a foreground heat and a textured body — a little habanero for top-note perfume, plus poblano for sweetness and glycerin-like mouthfeel.

One professional trick: design in layers.

Think in top notes (aroma) like habanero, scotch bonnet, and fresno; mid-palate body like jalapeño, serrano, and anaheim; and bass notes like rehydrated ancho/pasilla, roasted peppers, or small amounts of smoked chiles.

Fermentation can blur sharp edges, so slightly “too bright” at the start often becomes perfect in week two.

Mash vs Brine: Two Paths to Great Sauce

Most home hot sauce ferments fit one of two approaches:

1) Mash ferment (chopped peppers + salt, packed and weighted)

This is the most direct method: you ferment a pepper mash and then blend it into sauce.

Why it’s great: High flavor intensity (everything stays together), easy tasting and progress tracking, and a natural path to thicker sauces.

Watch-outs: You must keep solids submerged or pressed down, and oxygen exposure at the top can create kahm or mold.

2) Brine ferment (peppers submerged in measured saltwater)

This is common for pepper rings or whole peppers.

Why it’s great: Very stable when the brine is correct, easy to keep everything submerged, and you can use brine to dial final texture.

Watch-outs: Flavor can be a little less “dense” unless you blend solids well, and brine concentration needs accuracy.

Both are excellent. Mash ferments reward intensity; brine ferments reward stability.

The Science Made Practical: Salt, Temperature, and Time

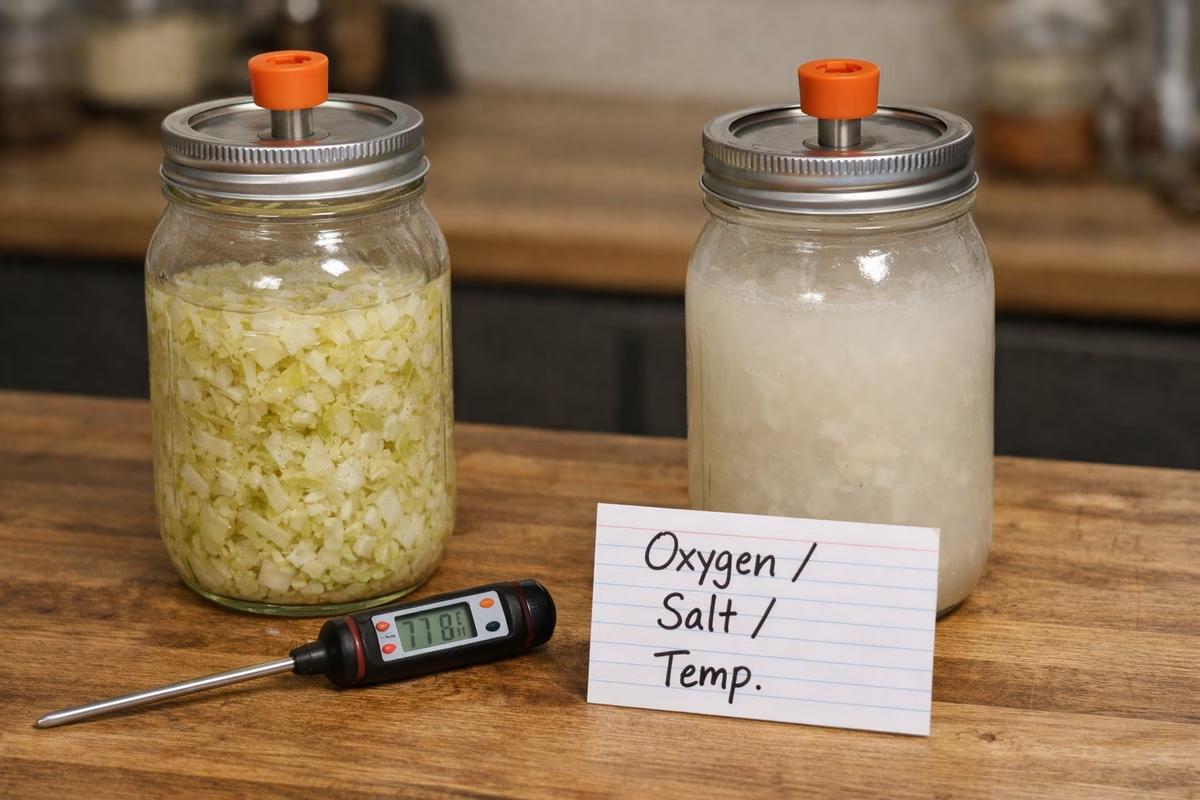

Fermentation is governed by three simple levers.

Salt is typically 2–3% by weight of peppers (2% tends to be brighter; 3% tends to be more controlled and slower). Weigh peppers, multiply by 0.02 or 0.03, and add that weight in salt; kosher salt (no iodine) is preferred. Temperature in the 18–22°C (64–72°F) range produces steady lactic fermentation; lower temps slow activity and favor delicate aromatics, while higher temps speed things up but increase risk of off notes. Time is where the flavor arc emerges: early bright acidity, then a middle phase of umami and complexity, then a later phase where funk increases. Many sauces feel “bright” around 5–7 days, “balanced” around 10–14, and “funk-forward” at 3+ weeks—taste beats the calendar.

Trust tasting more than the calendar: open the jar and taste day to day after the first 4–5 days.

Salt math you can trust

Two reliable ways to calculate salt:

In a mash, salt is a percentage of total fermentables (peppers plus any added produce). In a brine, salt is a percentage of water weight (and some people also lightly salt the peppers).

For a mash, 2–3% is a common range because it’s high enough to discourage spoilage and low enough to let lactic acid bacteria thrive.

For a brine, many people use 3–5% salt by weight of water for stability, especially with whole peppers. (Different peppers and climates tolerate different approaches; higher brine slows fermentation but increases control.)

If you’re new, choose the conservative path: 3% mash or 4% brine. You’ll still get great flavor.

Temperature: flavor vs speed

Lower temperatures tend to preserve more delicate aromatics and reduce aggressive fermentation character. Higher temperatures move quickly but can push the ferment toward sharper, sometimes less elegant notes.

If you can’t control temperature precisely, don’t panic—what matters most is avoiding extremes and keeping the jar out of direct sun.

pH, Safety, and the “When Is It Done?” Question

Fermentation is a preservation method, but you still want to think like a food safety professional:

Keep oxygen out (solids submerged, clean tools, no “floating islands” above brine). Prefer measurable confidence when you can: if you have pH strips or a meter, use them.

As a general safety benchmark, shelf-stable acidic foods are often below pH 4.6. Many pepper ferments land around pH 3.5–4.2 once active lactic fermentation has done its job.

But pH is not the only factor; sanitation and mold control matter too. If a jar grows colored mold or smells rotten/chemical, it’s not a “fix it later” scenario.

A Friendly, Fail-Safe Recipe (Batch ~1 kg peppers)

For a baseline batch, start with about 1000g peppers (stemmed and chopped) and 20–30g salt (2–3%). Optionally add 50–100g aromatics like onion, garlic, roasted carrot, or tomato. A small amount of neutral sugar or fruit can help lactic bacteria get started, especially in very low-sugar pepper blends.

Method

- Clean and chop peppers and aromatics. Weigh everything.

- Mix peppers with salt and optional sugar; rub briefly to draw juices.

- Pack tightly into a sanitized jar or crock, pressing to expel air. Add a weight to keep solids submerged beneath their brine.

- Keep at 18–22°C, taste after 5 days, then every 2–3 days. When acidity and flavor reach your target, proceed to finish.

Finishing

Blend the fermented mash with vinegar (apple cider or rice vinegar), a splash of neutral oil for silkiness, and a pinch of sweetness if needed—then adjust salt. If you want extra stability (or you’re gifting bottles where storage is unpredictable), you can simmer gently to arrest fermentation, though it will mute some volatile aromatics. Bottle, refrigerate, and enjoy; fermented sauces last months in the fridge.

Vinegar is a tool, not a crutch

Vinegar does three jobs:

It adds bright, high-tone acidity, helps stabilize the sauce, and thins texture without diluting flavor.

Use it intentionally. If your ferment is already beautifully acidic, you may only need a small amount for lift.

To pasteurize or not?

If you keep the sauce refrigerated, you can often skip heating and preserve more aromatic complexity.

If you need room-temperature stability (or you’re gifting bottles and can’t control storage), gentle heating can help stabilize—but it will mute some volatile floral notes.

There isn’t one right answer; it depends on how and where the sauce will be stored.

Variations & Creative Experiments

Fermented fruit heat (peach, mango, pineapple) can make a tropical, aromatic ferment; consider lower salt (around 2%) and taste early. For smoke, lightly roast some chiles before fermenting or add a small percentage of chipotle for persistent smoke. Barrel-style longer ferments (6–12 weeks) can build oxidative, savory depth. Backslopping—reserving 5–10% of a successful ferment as starter—can accelerate future batches and carry desirable microbes.

Flavor Architecture: Building a Sauce With a Point of View

The difference between “hot sauce” and “a sauce you remember” is often a deliberate flavor concept.

Try designing around one of these archetypes:

1) Citrus-forward brightness

Goal: punchy, clean, wakes up rich foods.

Design moves: A serrano/jalapeño base works well, with a light hand on garlic (too much can dominate). Finish with lime zest or a small splash of lime juice right before bottling for lift.

2) Tropical perfume heat

Goal: aromatic top notes under serious heat.

Design moves: Use habanero/scotch bonnet as the aromatic driver, add mango/pineapple in small percentages (taste early), and finish with rice vinegar if you want a lighter acidity profile.

3) Savory, umami depth

Goal: sauce that behaves like seasoning.

Design moves: Add roasted carrot or onion for sweetness and body, ferment longer (3+ weeks) for deeper savory notes, and finish with a touch of vinegar and salt adjustment rather than a lot of sugar.

4) Smoke as an accent

Goal: smoke present but not ashtray.

Design moves: Use smoked/dried chiles sparingly, and if you need more smoke, add it at finishing (a tiny pinch) rather than fermenting a huge amount.

You can also use herbs, but be careful: fresh herbs can go bitter in fermentation. Many makers prefer to add herbs at blending time and use the fridge to preserve their brightness.

Tasting Protocol: How to Read a Ferment

When evaluating, take small sips and note three things:

Top note (immediate aroma: floral, grassy, smoky), mid-palate (how acidity and heat interact: bright, blunt, hollow), and finish (length, savory notes, and whether unpleasant ammonia/medicinal notes persist).

Record pH if you have a meter: safe lactic ferments generally drop below pH 4.6, often in the 3.5–4.2 range.

Add one more professional lens: texture.

If the sauce feels thin and sharp, it may need body (carrot, roasted pepper, a small oil emulsion). If it feels thick and muddy, it may need lift (more vinegar, more fresh pepper aroma, or better straining). If heat blooms fast and vanishes, add a mid-palate pepper (serrano/jalapeño) or a tiny amount of sweetness to extend the finish.

Safety, Troubleshooting, and Bad-Jar Signs

Fermentation is forgiving but watch for red flags:

White kahm yeast is generally harmless; skim it, taste, and continue if flavors are fine. Slimy films or bright-colored molds (green, black) mean discard. Strong ammonia or rotten-egg smells are a warning; if caught early you can sometimes improve airflow and acidity, but if it’s severe, discard.

Use clean utensils, keep solids submerged, and maintain appropriate salt and temperature.

Common problems and what they usually mean

If a ferment is sluggish after 3–4 days, temperature may be low, peppers may be dry, or salt may be high—give it time and keep it clean rather than “fixing” it with random additions. If it tastes harshly salty, you can often rescue it at finishing by blending with unsalted ingredients, vinegar, or a little fruit/veg. If it tastes flat, you likely need more acidity or aromatics at finishing (vinegar, citrus zest, or a small amount of fresh pepper). If it tastes overly funky, shorten the fermentation window next time, keep temperatures slightly cooler, and taste earlier.

Culinary Applications and Pairing Ideas

Fermented hot sauce is a seasoning — it can be used like vinegar, miso, or soy sauce.

Use a few drops on eggs for brightness, stir a spoonful into grains and bowls for savory depth, reduce it with honey and citrus for sticky glazes, or add a dash to cocktails like a Bloody Mary or spicy margarita.

Two chef-y uses:

Try fermented hot sauce butter (whisk a teaspoon into soft butter for corn, steak, mushrooms, bread) or use it as a vinaigrette anchor—acid plus spice in one ingredient, sometimes replacing vinegar entirely.

Keeping Notes: A Short Lab Notebook Template

Track the basics: date, peppers, weights, salt %, temperature, days to target flavor, pH (if measured), finishing ratio (mash:vinegar), and tasting notes/pairings. The goal isn’t bureaucracy; it’s giving your future self a shortcut to what worked.

Final Thought: Patience, Play, and the Joy of Iteration

Fermenting hot sauce is a craft accessible to anyone with curiosity and a scale. Start small, keep notes, and remember that every jar teaches you something new — about peppers, microbes, and how a little salt and time can turn heat into music.

If you want, I can: 1) add an illustrated step-by-step with photos, 2) generate bottle label copy, or 3) create a printable lab-notebook template for tracking batches.