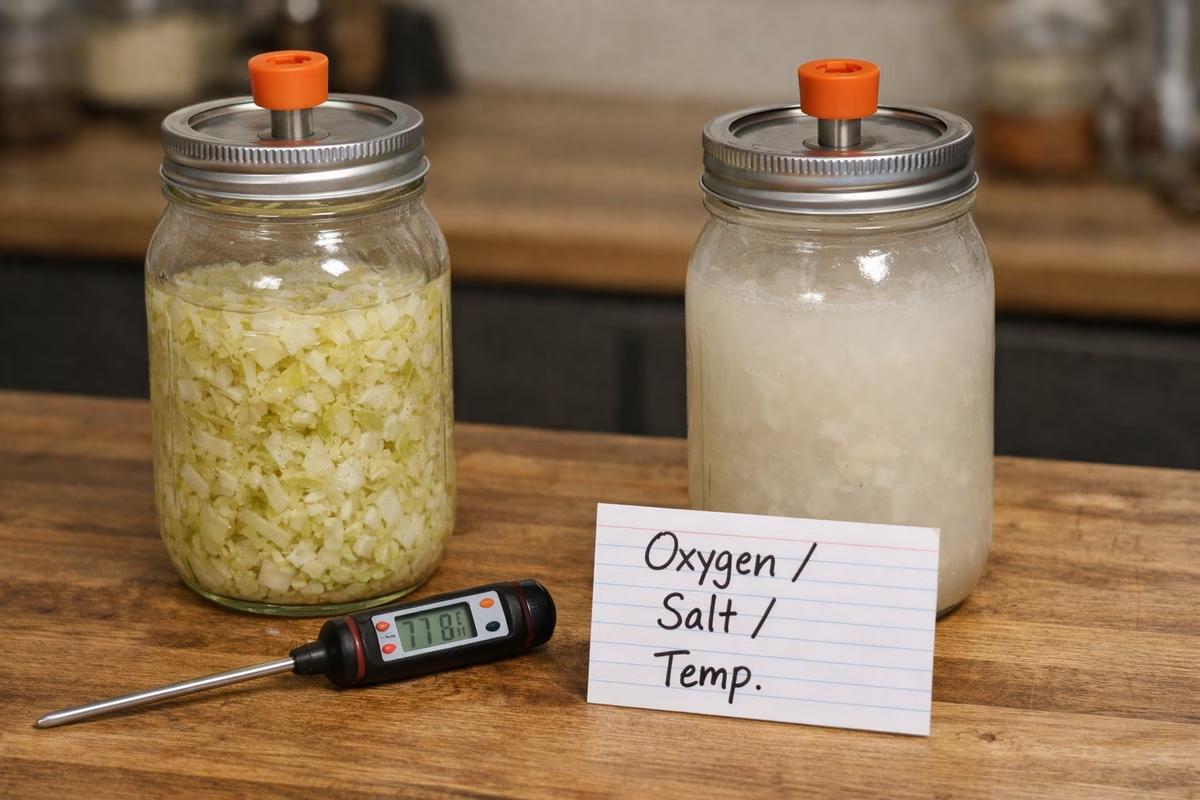

Fermented hot sauce is simple on paper: peppers, salt, time. In practice, most “problems” come from the same three causes: oxygen, inconsistent salt, or temperature swings. The fourth cause—less dramatic but common—is simply not knowing what normal fermentation looks and smells like.

This guide is built for real kitchens: a safe baseline so you can stop guessing, quick diagnosis when something looks weird, practical fixes when the batch is still worth saving, and clear lines for when to discard and restart.

If you’re brand new, read Fermentation Flavor Design first so you understand what “good” tastes like.

The safe baseline (so you stop guessing)

When people get anxious about ferments, it’s almost always because one of these basics was not controlled.

Salt: aim for 2.5–3.5% by weight for most pepper ferments. (If you’re doing a brine ferment rather than a mash, you still want your total salinity to land in a similar ballpark.)

Submersion: solids stay below brine. Oxygen is the enemy of clean flavor.

Container: clean jar, airlock or loose lid (burp daily if sealed).

Temperature: ~18–22°C (65–72°F) is a forgiving zone. Warmer speeds fermentation but increases risk of soft textures and harshness.

Smell: lactic/tangy is normal; putrid/rotten is not.

If you want a single rule that prevents most disasters: keep solids submerged.

Salt math (the #1 source of confusion)

Most ferment problems start with “I eyeballed it.” Measuring is boring, but it buys you calm.

Two practical approaches:

Approach A: mash ferment (peppers chopped/blended with salt).

Weigh your peppers + any vegetables/fruit going into the mash. Multiply by your target salt percentage.

Example: 1000 g total mash at 3% → 30 g salt.

Approach B: brine ferment (solids submerged in salt water).

Make a brine by weight (for example 30 g salt per 1000 g water for ~3%), then pack your jar and cover. The jar will not be perfectly exact, but a correctly made brine plus good submersion is very forgiving.

If you’re unsure which method you’re doing, choose brine for beginner batches. It’s easier to keep the system stable.

What “normal” looks like (and why it matters)

Fermentation doesn’t always look cinematic. Some batches bubble hard. Some barely show activity. Many “no bubbles” ferments are still fine.

Normal signs include:

- A steady, clean lactic smell (like pickles, yogurt tang, or sourdough).

- A little fizz when you stir or tilt.

- Color changes as peppers soften.

- Sediment collecting at the bottom.

Less normal signs include:

- Fuzzy growth.

- Rotten/putrid smell.

- Repeated surface growth because solids keep floating.

Also normal (and often mistaken for “something wrong”):

- Cloudy brine in the first week.

- White sediment collecting at the bottom.

- A ring around the jar where brine splashed and dried.

Those are usually signs of activity, not contamination.

Kahm yeast vs mold (what you’re actually looking at)

Most “mold panic” is actually kahm yeast.

Kahm yeast

Kahm is a surface yeast that appears when there’s oxygen access.

Often:

- Thin white film

- Wrinkly/flat “skin” on top of brine

- Smells yeasty or slightly funky, not rotten

What to do:

- Skim it off.

- Ensure solids are submerged and the jar is not overfilled.

- Reduce oxygen exposure (use an airlock; improve the seal).

- Taste later—many ferments are still excellent.

Kahm is usually a flavor risk (it can dull aromas), not a safety emergency.

Mold

Mold is the one thing you should treat with respect.

Often:

- Fuzzy growth

- Blue/green/black/pink patches

- Growing on exposed solids above brine

What to do:

If you have fuzzy mold or anything clearly colored and spreading, the safest move is to discard the ferment. People argue about salvage, but hot sauce is not worth gambling.

“My brine level dropped” (evaporation, leaks, or absorption)

Sometimes brine seems to vanish: vegetables absorb it, the jar wasn’t sealed well, or the room is warm and dry.

What matters is the outcome: are your solids still submerged?

Fix:

- If solids are exposed, top up with a similar-salinity brine (don’t top up with plain water).

- Improve the seal/airlock so you’re not slowly losing liquid.

- Use a weight so solids don’t rise when liquid level changes.

“It’s too sour / too sharp”

Sharpness is usually an imbalance, not a failure.

Common causes:

- Ferment ran long and built lots of acid

- High temperature sped activity

- Too little sweetness/body to balance acidity

Fixes that actually work:

- Blend with body: roasted carrot, red bell pepper, tomato, or cooked onion can round sharpness.

- Add a small sweetness: fruit, honey, or sugar (start tiny, taste, repeat).

- Use vinegar strategically: it adds brightness but can make sharpness feel sharper—don’t “fix sour with more sour.”

- Dilute with a mild base: blend a portion of your ferment into a fresh cooked sauce to keep complexity without the edge.

Advanced note: if the ferment tastes “thin” and sharp, it often needs body more than it needs sweetness.

“It’s not sour enough yet” (underdeveloped ferment)

If the ferment smells clean but tastes like “salty pepper water,” it may simply be early.

What to do:

- Give it more time at a stable, moderate temperature.

- Keep solids submerged and avoid stirring excessively (stirring introduces oxygen).

- Taste every few days and look for the moment it goes from “pepper” to “pepper + tang + depth.” That’s your flavor peak.

“It tastes flat / one-note”

Flat ferments are often either underdeveloped or oxygen-exposed.

Common causes:

- Under-fermented (not enough time)

- Too much oxygen exposure (aroma loss)

- Too much vinegar added early

Fix:

- Give it more time (if it’s early and smells clean).

- Keep it anaerobic (submerge solids, use an airlock).

- Add vinegar at the end and in small doses, tasting between additions.

- Add aromatics after fermentation (garlic, citrus zest, herbs) for lift.

If it’s flat because it lacks salt, correct salt first before chasing complexity.

“The ferment stopped bubbling”

Not necessarily a problem. Many ferments are most active in the first days, then calm down.

Check:

- Are solids still submerged?

- Does it smell clean (lactic/tangy)?

- Is there still gentle pressure when you open the jar?

Fix:

- If it’s cold, move it to a slightly warmer spot.

- If salt is extremely high, you may have inhibited activity; in the future weigh salt.

- If you used chlorinated water, switch to filtered water next time.

If it smells clean and tastes like it’s progressing, “no bubbles” is often just “less visible fermentation.”

“It tastes alcoholic / boozy”

Sometimes you’ll smell a cider/beer-like note. This can happen when yeasts are more active than lactic bacteria, often influenced by oxygen exposure, lots of sugar (fruit-heavy recipes), or warmer conditions.

What to do:

- Tighten up the anaerobic setup (better submersion, airlock).

- Ferment cooler.

- Keep fruit additions modest in early experiments.

If the batch still smells clean and lactic underneath, it can often settle out after blending and a bit of fridge time.

“Soft/mushy peppers” or “slimy brine”

Texture issues can be normal or a warning sign depending on smell and severity.

Common causes:

- Too warm + too long can break down texture

- Some vegetables naturally thicken (or release pectin)

- Contamination can create unpleasant textures

Fix:

- Blend and strain for a clean sauce texture.

- Use a bit of vinegar at finish to tighten perception.

- For future batches: ferment cooler and don’t push time past the flavor peak.

If it smells rotten or the texture is truly off-putting, discard and restart with cleaner equipment and stricter submersion.

“It smells like sulfur / eggs”

Sometimes ferments throw off sulfur notes—often related to stress (temperature swings, unusual ingredients, or yeast activity).

First check the fundamentals: temperature and oxygen. If the batch smells clean underneath the sulfur note (still lactic, not rotten), it’s often fixable by finishing techniques: blending with roasted aromatics, adding a little sweetness/body, and giving it time in the fridge.

If the smell is truly putrid, discard.

“It’s too salty”

Over-salting usually doesn’t make a ferment unsafe; it makes it slow and hard to enjoy.

Options:

- Blend the finished ferment with unsalted body ingredients (roasted peppers, carrots, tomatoes) to dilute salt while keeping flavor.

- Use the sauce as a concentrate: a small spoon into soups, beans, marinades.

For the next batch, weigh salt and don’t rely on volume measurements.

Brine level, weights, and the float problem

The most common mechanical failure is floating solids. Floating solids get oxygen. Oxygen creates surface growth. Then you’re troubleshooting when you should be fermenting.

Practical fixes:

- Use a fermentation weight.

- Leave headspace so brine can expand without pushing solids up.

- If you have a mash ferment, consider switching to a brine ferment for beginner batches—it’s easier to keep everything submerged.

Sanitizing: clean vs sterile

You don’t need a laboratory, but you do need to be consistent.

- Wash jars, lids, weights, utensils with hot soapy water.

- Rinse well so you don’t leave soap residue.

- Keep your workspace tidy so you’re not constantly introducing new microbes.

Most of the time, the real “sanitation” is submersion and salinity.

Bottling: the moment most people ruin a good ferment

Common mistake: adding a lot of vinegar, skipping salt balance, and bottling without tasting the final blend at room temperature.

A calm workflow:

- Blend fermented mash with a small amount of brine.

- Taste and adjust salt.

- Add vinegar in small additions until it tastes bright—not thin.

- Add body (roasted pepper/carrot/tomato) if it tastes sharp.

- Strain if you want a smoother pour.

- Bottle, label the date, and refrigerate.

If you’re aiming for a shelf-stable sauce, you’ll want to be much more deliberate about acidity and bottling sanitation. If you’re keeping it refrigerated, you have more flexibility.

When to stop and start over

Discard if:

- You see fuzzy/colored mold

- It smells like rot, sewage, or “dead” food

- You can’t keep solids submerged and mold keeps returning

Fermentation is cheap. Your stomach isn’t.

Next steps

Build a deliberate three‑bottle shelf: one bright vinegar sauce, one fermented depth bottle, and one fruity‑hot sauce that climbs without punishing. Use the Hot Sauce Database for profiles, then train instinct with Ferment Frenzy.