Hot sauce gets better the moment you stop asking “how hot is it?” and start asking a more useful question: what is it doing to the food?

Great hot sauce doesn’t just hurt. It adds lift when a dish feels heavy, wakes up aromas that are hiding, and leaves a finish that makes the next bite feel new. Heat is only one part of that. In fact, for most people, the “I don’t like hot sauce” problem is really one of these:

- The sauce is sharp in a way that doesn’t match the dish.

- The heat climbs in a way that feels unpleasant (fast spike, long burn).

- The sauce is being used as a topping when it should be used as an ingredient.

This quickstart is a calm on-ramp. It teaches you how to taste any sauce in under a minute, how to predict what it will pair with, and how to build a small shelf that covers almost everything without becoming a collector.

A simple mental model: frame, heat curve, balance

When you taste hot sauce, you’re trying to answer three questions.

What’s carrying the flavor?

How does the heat behave over time?

What does the sauce need to feel “complete”?

If you can answer those, you can use the sauce well—even if you can’t name the pepper, the region, or the exact Scoville number.

The 60-second tasting method (that works on a spoon)

You don’t need a tasting wheel. You need a repeatable ritual.

Start with a tiny amount on a spoon (or a corner of a tortilla chip). Take a small taste and wait ten seconds before you take a second bite. That pause matters because heat is time-based.

1) Frame: what’s carrying the flavor?

“Frame” is the base flavor architecture. It’s the thing you notice even before heat arrives.

Most sauces fall into one dominant frame (even if they have complexity). Here are the frames you’ll see everywhere, and what they tend to be good at.

Vinegar-forward.

These sauces are bright, sharp, and immediately clarifying. They excel at cutting fat (fried chicken, rich pork, creamy sauces) and waking up foods that feel sleepy. The tradeoff is that vinegar-forward sauces can feel harsh if you use too much or if the dish is already acidic.

Fermented tang.

Fermentation tends to create rounder acidity and savory complexity. Fermented sauces often feel less sharp than vinegar-forward styles, with a deeper tang that integrates well into eggs, sandwiches, and soups. If vinegar sauces feel “pointy” to you, fermentation is often the answer.

Fruit-forward.

Fruit can be literal (mango, pineapple, berries) or perceived (a naturally fruity pepper). Fruit-forward sauces are great for grilled meats, seafood, and anything that benefits from a sweet-acid top note. The key is balance: the best fruit sauces taste like fruit and pepper, not like jam with heat.

Smoke and roast.

Smoky sauces bring depth. They’re the ones you reach for when a dish tastes thin or when you want “barbecue energy” without actually doing barbecue. Smoke pairs naturally with beans, stews, roasted vegetables, and meats. The risk is overuse: too much smoke can flatten everything into one note.

Garlic/umami.

Some sauces lean into savory aromatics: garlic, onion, miso-like funk, tomato, or anchovy-style umami (without necessarily containing fish). These sauces shine in noodles, pizza, roasted vegetables, and dishes where you want a savory punch more than a bright one.

If you can name the frame, you can predict the best use case. It’s the difference between “I like this sauce” and “I know what this sauce is for.”

2) Heat curve: how does it climb?

Heat isn’t one sensation. It’s a timeline.

Notice three aspects:

Speed. Does the heat hit immediately, or does it build after a few seconds? Fast heat can feel exciting in tiny doses and punishing in big ones. Slow-building heat often feels more “culinary” because it gives flavor time to arrive.

Shape. Does it spike and fade, or does it linger? Lingering heat isn’t automatically bad, but it changes how you want to use the sauce. A long linger can dominate a meal if you keep adding more.

Cling. Thick or oily sauces cling to the mouth and can feel hotter because they stick around. Thin, watery sauces can feel brighter and easier to distribute across food.

When you learn your preferred heat curve, buying becomes easier. Some people love a quick spark that disappears. Others enjoy a slow, steady build. Either is valid; the trick is choosing sauces that behave the way you enjoy.

3) Balance: what does the sauce need?

If a sauce feels “off,” it’s usually a balance problem.

If it tastes too sharp, it may need body or sweetness—not more vinegar. Try it with fat (mayo, yogurt, avocado) or mix a small amount into a dish rather than topping.

If it tastes too sweet, it often needs salt or acid to sharpen the edges. On food, sweetness can be corrected by pairing with something salty or smoky.

If it tastes too harsh, the fix is frequently dilution and context. Stir it into soup, whisk it into a dressing, or fold it into mayo. Harsh sauces often become great when they’re used as ingredients.

This is the key insight that makes hot sauce feel “culinary” instead of chaotic: you’re not just adding heat; you’re adjusting balance.

How to choose your next bottle (one reliable rule)

The fastest upgrade is to buy for contrast, not “more of the same.” If you already own a sharp vinegar cayenne, buying three more sharp vinegar cayennes won’t teach you much.

Instead, pick three roles that cover most meals. Think of them like tools.

Role 1: the green bright sauce

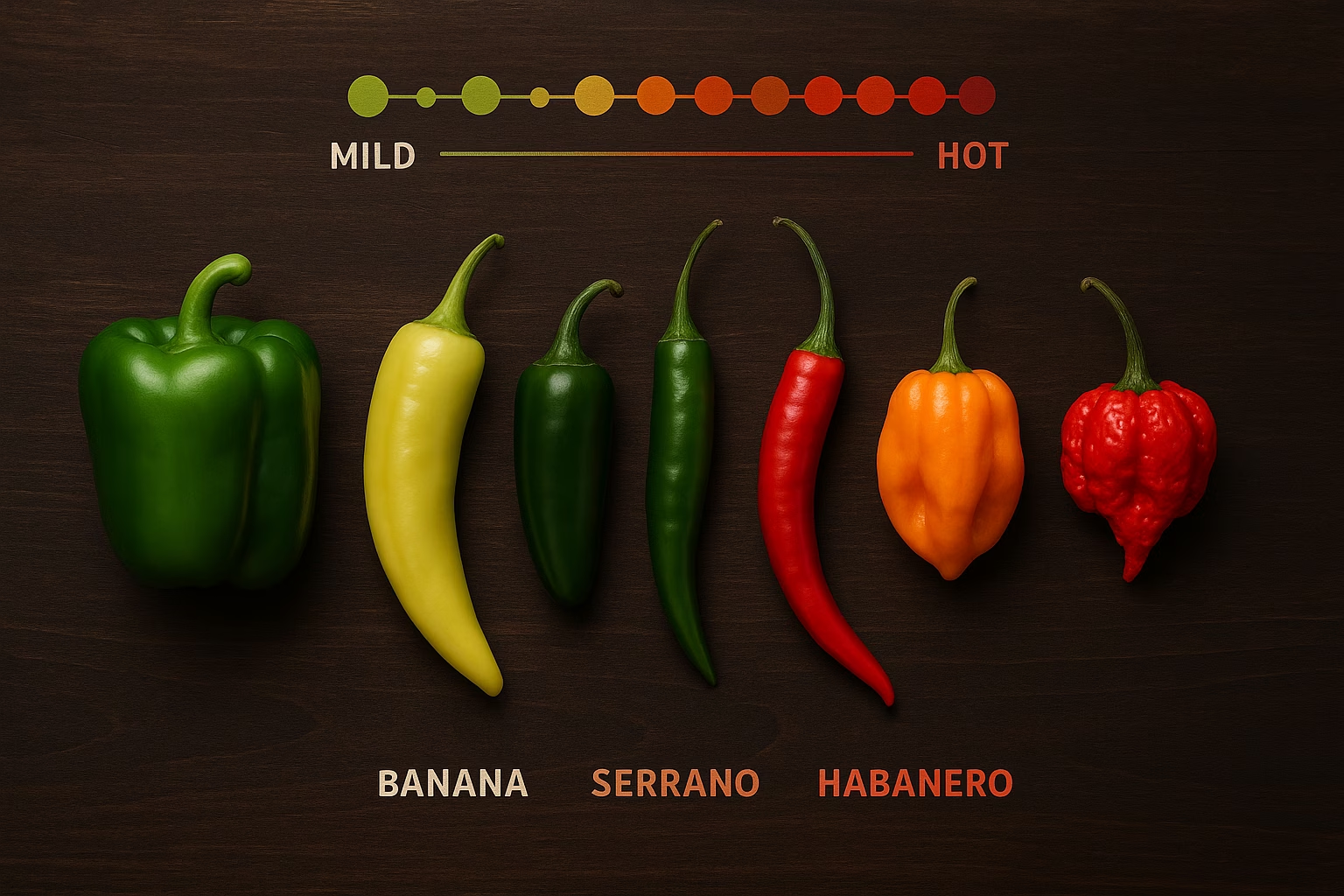

This is your fresh, lively, everyday sauce. It should feel crisp and aromatic rather than heavy. Jalapeño and serrano styles often live here. They’re excellent for eggs, tacos, grain bowls, roasted vegetables, and quick meals.

Role 2: the depth sauce

This is your “make it taste like more” bottle. It can be smoky, roasted, or classic vinegar-forward. It’s great for soups, beans, stews, pizza, barbecue-adjacent meals, and anything rich.

Role 3: the aromatic hot sauce

This is where you go when you want heat that also smells like something. Habanero and Scotch bonnet styles often bring an aromatic fruitiness that can make a dish feel brighter and more alive—even when the heat is significant.

When you shop, use the Hot Sauce Database to match bottles to these roles. You’re building a small system, not just accumulating random heat.

The tiny shelf that covers almost everything

If you only keep three sauces, start with a clean, contrasting trio:

For bright daily use, try a green sauce like Jalapeño Verde or Serrano + Lime. These tend to work like fresh herbs: they lift.

For depth, choose something that adds bass notes. A classic like Louisiana-Style Cayenne is a workhorse, and a smoky option like Chipotle Smoke can make simple food taste intentional.

For aromatic heat, choose a bottle that brings perfume as well as burn, such as Habanero + Fruit or Scotch Bonnet.

If you want a fourth bottle that often becomes someone’s “forever table sauce,” add a fermented option for tang without sharpness, like Fermented Fresno or Garlic-Fermented Red.

How to use hot sauce so it tastes better (not just hotter)

Most people only use hot sauce as a final drizzle. That’s fine, but it’s not the only move.

Here are three ways to make hot sauce feel integrated:

1) Mix it with fat for a stable “heat sauce.”

Stir a little hot sauce into mayo, yogurt, sour cream, or mashed avocado. Fat smooths harsh edges, carries aroma, and creates a sauce you can spread and control. This is how you turn a very hot sauce into something you can actually enjoy.

2) Add it earlier for flavor, later for brightness.

If you put hot sauce into a stew early, you get integrated heat and deeper flavor. If you add it at the end, you get brightness and aroma. Both are valid; choose based on what the dish needs.

3) Treat it like acid: add, taste, stop.

Hot sauce behaves like acid and salt. You add a little, taste, then decide if the dish needs more. The goal is not maximum heat; it’s the point where the food tastes more alive.

A small practice drill (two minutes, once)

If you want to train your instinct quickly, do this once with any two sauces:

Taste Sauce A on a plain chip. Wait ten seconds. Notice frame and heat curve.

Taste Sauce B the same way.

Now taste both again, but this time mix each with a little mayo. Notice which one becomes smoother, which one becomes muted, and which one becomes more aromatic. You’ll learn a lot about how that sauce wants to be used.

Next steps

If you want to understand why heat numbers don’t always match your experience, read Understanding the Scoville Scale. If you want to make sauce (and understand it at a deeper level), start with Making Hot Sauce. If you want fast drills that build real intuition, the Heat games are short and surprisingly effective.