What is the Scoville Scale?

The Scoville scale is a way of talking about heat with numbers. It measures the pungency (spiciness) of chili peppers and spicy foods in Scoville Heat Units (SHU).

It’s useful, but it’s also easy to misunderstand.

If you’ve ever bought a sauce that claimed a terrifying SHU and found it oddly manageable—or bought something “mild” that wrecked you—this guide is for you. You’ll learn what SHU is actually measuring, why it doesn’t perfectly predict experience, and how to use the scale in a practical way when choosing peppers and sauces.

How it works (then and now)

The Scoville scale was created in 1912 by pharmacist Wilbur Scoville. The original method was a sensory test: tasters diluted pepper extract in sugar water until heat was no longer detectable. The more dilution required, the higher the number.

Today, SHU values are typically derived from lab measurement of capsaicinoids (the compounds responsible for heat) and then converted into an SHU equivalent.

This matters because the number is anchored to chemistry, but your experience is anchored to your body and the food context.

Capsaicin is the source of heat (but heat is a delivery system)

The chemical headline is capsaicin. But “how hot it feels” depends on how capsaicin is delivered.

Think of SHU as the concentration of heat potential. Your experience depends on the delivery method:

- thin and vinegary sauces spread quickly but may not cling,

- thick or oily sauces cling and feel more intense per bite,

- powders can disperse differently,

- cooked vs raw peppers can taste and feel different,

- fermented sauces can feel smoother even when hot.

So SHU is real—but it’s not the whole story.

Why SHU varies (even for the “same pepper”)

One reason the Scoville scale can feel inconsistent is that peppers aren’t manufactured widgets. Heat can vary from pepper to pepper.

Common reasons include:

- Genetics and cultivar: “habanero” is a category, not a single identical plant.

- Growing conditions: sunlight, water stress, and soil can influence capsaicinoid development.

- Ripeness: ripe peppers can taste different and sometimes feel hotter.

- Pepper anatomy: a lot of capsaicin is concentrated in the internal tissues (pith/placenta), not evenly distributed.

That’s why tables are ranges. The ranges are real; the precision is not.

Pepper anatomy (the fast explanation that helps cooking)

If you want to control heat in cooking, it helps to know where heat lives.

Most of the capsaicin is concentrated in the pepper’s internal membranes and pith (often called the placenta region), not primarily in the seeds themselves. Seeds can carry heat because they contact those tissues, but removing seeds alone doesn’t always remove the burn.

Practical implication: if you want a pepper’s flavor with less heat, remove the internal membranes/pith as well.

“It says 1,000,000 SHU, why doesn’t it feel like it?”

Even when the chemistry is high, experience can be moderated by context:

- Dilution: a sauce can include a super-hot pepper but at a low percentage.

- Sweetness and acidity: can change how heat is perceived and how long it lingers.

- Fat content: can carry aroma and change mouthfeel.

- Portion size: if you only use a drop, you may never feel the full potential.

This is why the most practical way to use SHU is role-based, not ego-based.

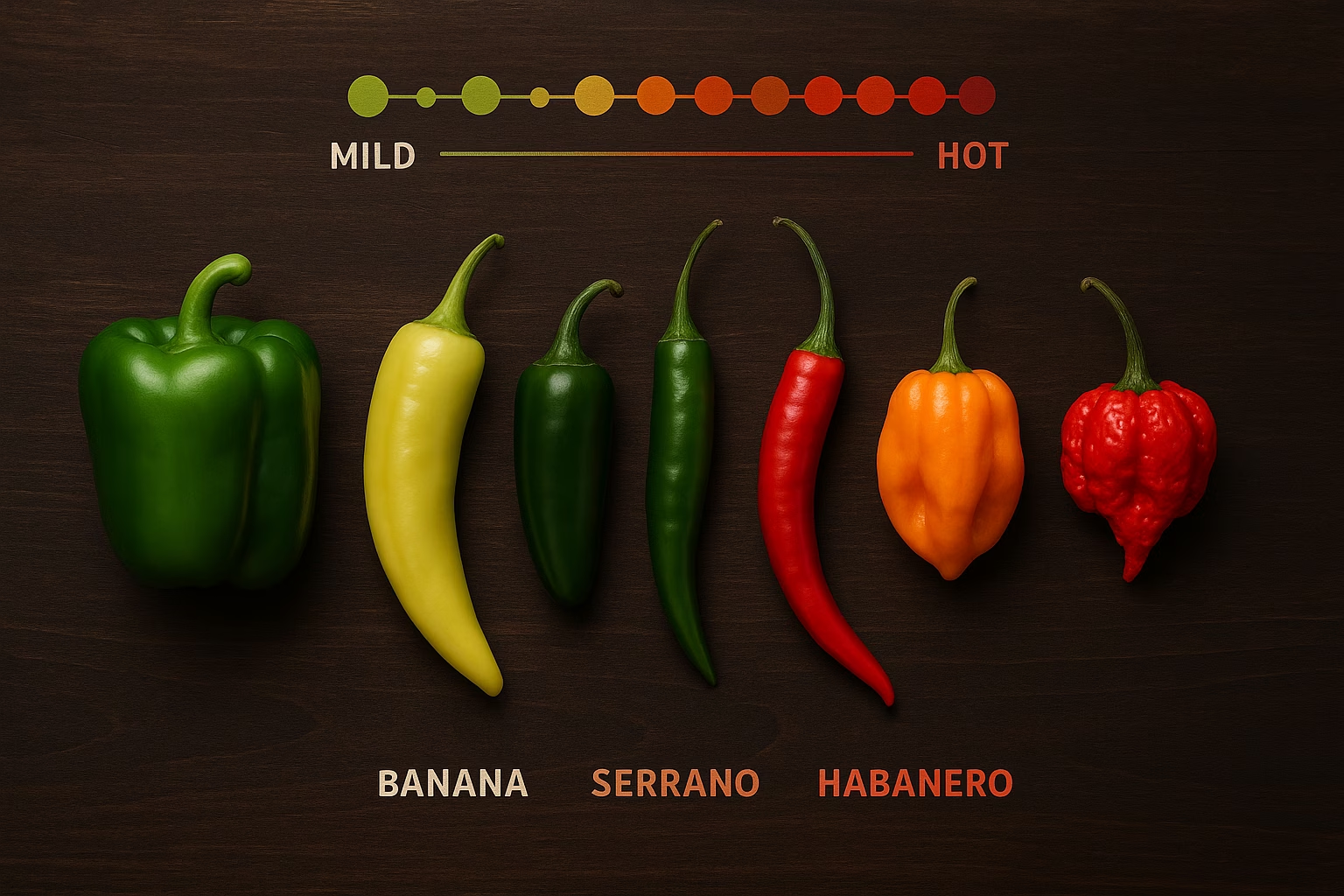

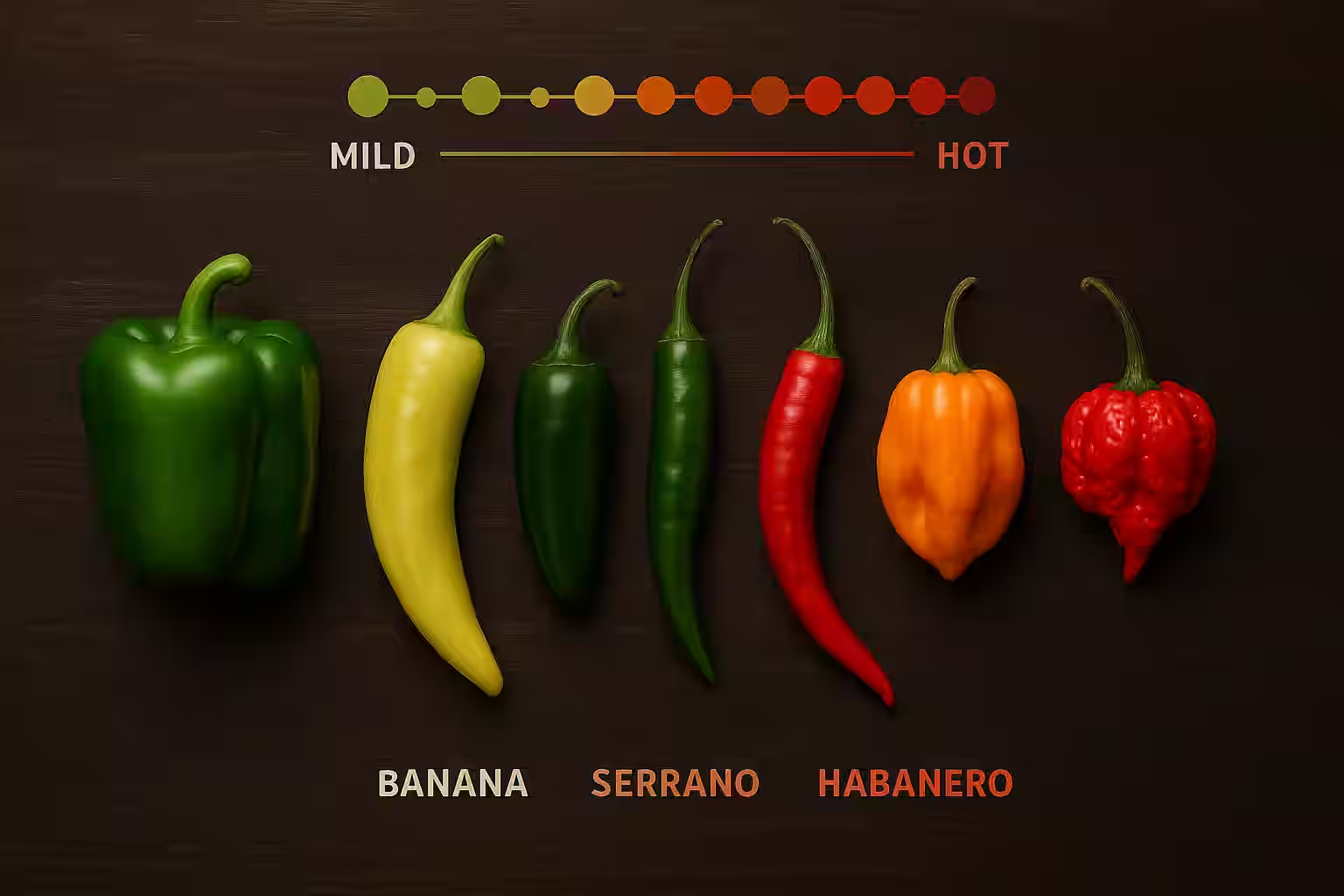

Pepper heat levels (useful ranges, not absolute promises)

Pepper heat ranges vary because peppers are agricultural products. Even within the same pepper type, heat can vary based on growing conditions, ripeness, and genetics.

Still, ranges are useful for orientation:

| Pepper | Scoville Heat Units |

|---|---|

| Bell Pepper | 0 |

| Banana Pepper | 0-500 |

| Jalapeño | 2,500-8,000 |

| Serrano | 10,000-25,000 |

| Cayenne | 30,000-50,000 |

| Habanero | 100,000-350,000 |

| Ghost Pepper | 855,000-1,041,427 |

| Carolina Reaper | 1,400,000-2,200,000 |

What SHU feels like in practice (a better mental model)

If you want a practical model, think in terms of usable dose, not maximum heat.

Two sauces can have the same SHU but behave differently:

- One might be so sharp and thin that you only use a few drops.

- Another might be balanced and flavorful, letting you use a full spoonful.

The second sauce can deliver more total capsaicin per meal simply because you use more of it.

Your experience also depends on:

- how the pepper is used (fresh vs cooked vs fermented),

- how the heat is carried (watery vs oily vs thick),

- how fast you eat (stacking heat is real),

- your tolerance (which adapts with exposure).

As a rough mapping for planning (not bravado):

- 0–2,500 SHU: pepper flavor, little burn; good for everyday finishing.

- 2,500–30,000 SHU: clear heat, controllable; great for table sauces.

- 30,000–100,000 SHU: noticeable burn; best in smaller doses or mixed into food.

- 100,000+ SHU: intense; often best as an ingredient rather than a blanket.

Finding your heat level (without turning meals into endurance sports)

The goal is not to “level up” for its own sake. The goal is to find the heat range where you can still taste.

Start mild, then climb slowly:

Beginner: 0–2,500 SHU

Intermediate: 2,500–30,000 SHU

Advanced: 30,000–100,000 SHU

Expert: 100,000+ SHU

If you jump too fast, you train yourself to associate hot sauce with pain rather than flavor. If you climb slowly, you learn what different peppers taste like.

Hot sauce vs raw peppers (why SHU gets weird)

Hot sauce heat varies based on:

- type of peppers used,

- amount of peppers,

- dilution with vinegar, fruits, vegetables, or water,

- processing methods.

Two important implications:

A “habanero sauce” can be mild if it’s heavily diluted or sweetened.

A “jalapeño sauce” can feel surprisingly hot if it’s thick, oily, or used in large amounts.

How to use SHU to pick a sauce (the practical workflow)

Treat SHU as a range, then choose based on use case.

Finishing (eggs, tacos, bowls)

For finishing, you usually want mild-to-medium heat so you can use enough sauce to taste the sauce itself.

If the sauce is too hot to use generously, it becomes a “dropper sauce,” which is a different role.

Cooking (stews, beans, marinades)

For cooking, you can go hotter because dilution happens in the pot. You can also choose peppers that bring specific flavors.

Mixing (mayo, ranch, butter)

Mixing is a cheat code. Fat carries flavor and softens the edge. This is how you make very hot sauces usable.

If you want a friendly way to use high-SHU sauces, mix them with mayo or yogurt first.

When SHU isn’t listed

Many sauces don’t list SHU. Use label cues:

- pepper listed first + few diluters → likely hotter

- lots of fruit/sugar or a very thin vinegar base → likely milder per spoonful

- oily or paste-like sauces often feel hotter because they cling

For profile-based shopping beyond numbers, use the Hot Sauce Database.

Choose by role: table sauce, cooking sauce, or “dropper”

Instead of asking “How hot is it?”, ask “What role do I want this sauce to play?”

Table sauce

Table sauces are meant to be used in spoonfuls, not drops. They should have flavor you can taste at the dose you want.

For many people, this sits roughly in the mild-to-medium zone, but the exact SHU isn’t the point. The point is: you can use enough for flavor.

Cooking sauce

Cooking sauces can be hotter because they’ll be diluted across a pot, a marinade, or a batch of food. This is also where you can choose peppers for flavor rather than pure heat.

Dropper sauce (super-hot concentrate)

Very high SHU sauces often work best as concentrates: you add a drop or two to a bowl, a soup, or a mayo.

This is a great role when you want intense heat without drowning the dish in vinegar or sweetness.

The mistake is trying to use a dropper sauce like a table sauce. It turns dinner into a dare.

Heat management (so you can keep tasting)

If you overheat your palate, everything after tastes like “hot.” That’s not tasting; that’s endurance.

Use these tools:

- Fat helps (yogurt, sour cream, avocado, mayo): capsaicin is fat-soluble.

- Starch dilutes (rice, bread, tortillas): spreads heat out over more bites.

- Acid brightens but doesn’t cancel heat (lime, vinegar): it can make heat feel sharper.

- Water doesn’t help much and can spread capsaicin around.

If you’re training tolerance, keep sessions short and stop before you lose the ability to taste nuance.

Handling super-hots safely (kitchen-level caution)

Super-hot peppers and very hot sauces deserve respect.

- Use gloves if you’re chopping very hot peppers.

- Avoid touching your eyes or face during prep.

- Keep ventilation reasonable if you’re heating or cooking very hot peppers; aerosolized capsaicin is unpleasant.

- Clean cutting boards and knives well after handling.

Heat is fun when it’s controlled. It stops being fun when it becomes accidental.

Ride the Heatwave

Balance the burn in a quick canvas mini-game that echoes the Scoville climb.

Next steps

- Explore our Hot Sauce Database

- Take the Heat Tolerance Quiz

- If you want a broader foundation on using sauces well, start with Hot Sauce Quickstart