Hot sauce is forgiving, but it’s not magic. The difference between “bright for months” and “mysteriously flat (or scary)” is usually not the pepper—it’s a handful of habits: clean handling, stable acidity, smart storage, and knowing what you can and can’t claim.

This guide is intentionally practical. It’s not a substitute for formal food-safety training. But it will keep most home makers and hot-sauce fans safely inside the lane while also protecting what you actually care about: flavor, aroma, and consistency.

If you do only one thing after reading this: treat unknown homemade sauces as refrigerated and stop trusting vibes.

The simplest safe mindset

If you’re not testing and not hot-filling, treat homemade hot sauce as refrigerated.

That’s not a failure. It’s a high-safety, high-quality choice.

Refrigeration:

- keeps aroma brighter (especially in fresh green sauces),

- slows unwanted fermentation,

- reduces the risk of spoilage,

- and gives you more predictable texture over time.

If you want to make shelf-stable sauce, you can—but you should do it intentionally, with measurement and process.

What makes hot sauce stable (and what “stable” actually means)

When people say “shelf-stable,” they usually mean two things:

The sauce stays safe at room temperature.

The sauce stays good at room temperature.

Those are different goals. A sauce can be safe and still lose brightness quickly. A sauce can taste amazing and still be unsafe at room temp if it wasn’t made and handled correctly.

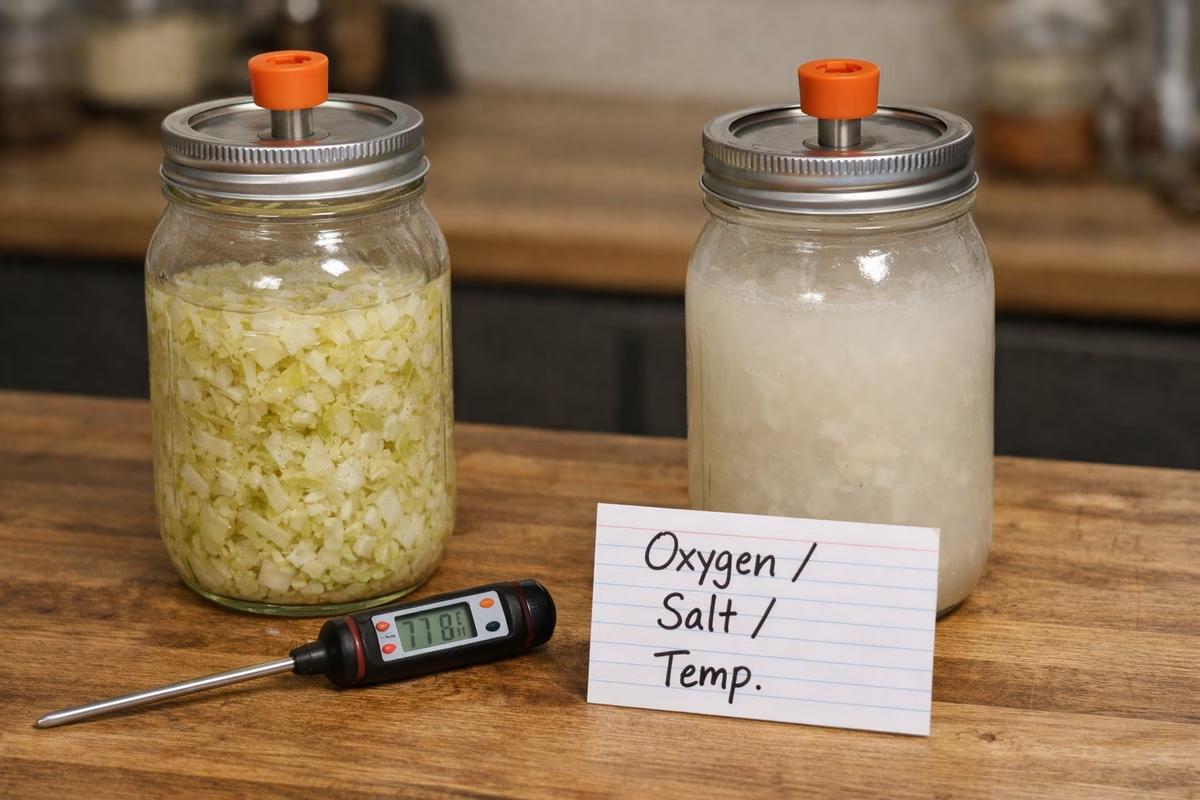

In practice, hot sauce stability often comes from a combination of:

- Low pH (high acidity) from fermentation and/or vinegar

- Salt (preservation and flavor)

- Clean handling (contamination is real)

- Appropriate processing (how it’s bottled and stored)

Texture can trick you. A thick sauce can feel “solid” and therefore safe, but thickness doesn’t guarantee stability.

A note on pH targets

Many makers aim for pH < 4.0 for shelf stability. Some aim lower for extra margin.

If you don’t have strips or a meter, don’t claim shelf-stable. Refrigerate.

That’s not gatekeeping; it’s acknowledging that you can’t see acidity with your eyes.

The three big enemies of hot sauce

Most storage problems come down to these.

1) Oxygen

Oxygen steals freshness. Over time it dulls aromatics and can shift color. It also supports certain spoilage pathways.

What to do:

- Keep caps tight.

- Avoid storing bottles half-open.

- Don’t pour sauce back into a bottle after it has touched food.

2) Heat and light

Heat accelerates flavor loss. Light can degrade color and aroma.

What to do:

- Store bottles in a cool, dark place.

- Don’t keep sauces next to the stove if you care about brightness.

- Refrigerate fresh sauces and fruit sauces.

3) Contamination

The most common way a sauce goes wrong is not “bad recipe.” It’s dirty handling: a spoon that touched food, a funnel that wasn’t clean, a bottle that wasn’t properly washed, or a cap with residue.

What to do:

- Pour; don’t dip.

- Keep bottle necks clean.

- Use clean utensils every time.

Refrigeration: friend, not failure

Refrigeration is the default for many of the best-tasting sauces.

Fresh green sauces—especially those built on herbs, scallion, lime, or fresh peppers—lose their high notes quickly at room temp. Cold keeps them vivid.

Fruit-forward sauces are also more likely to change in the bottle because sugar can encourage activity if conditions allow. Refrigeration reduces the odds of surprise.

Even fermented sauces often taste better refrigerated because cold preserves aromatic detail and slows ongoing fermentation.

If a bottle says “refrigerate after opening,” don’t interpret that as a warning; interpret it as a quality instruction.

Clean bottling workflow (the boring part that saves your batch)

If you make sauce at home, bottling hygiene is the difference between consistency and chaos.

Here’s a simple workflow that works well for most people:

Wash bottles, caps, and tools, then rinse well.

Let everything dry completely. Water can dilute, and moisture can create weird outcomes.

Keep a “clean zone” on the counter: funnel, bottles, ladle, caps.

Bottle with a funnel you trust, and wipe the neck before capping.

Label date, pepper, and style (fresh / fermented / vinegar-forward / fruit).

Store cold unless you have tested and processed appropriately.

This looks boring because it is boring. It also prevents most “mystery failures.”

Shelf life by sauce style (realistic expectations)

Different sauce styles age differently, even when they are safe.

Fresh sauces

Fresh sauces are built on immediate flavor: raw peppers, fresh herbs, citrus, raw garlic.

They often taste best early. Expect brightness to fade first, even if the sauce remains edible.

If you care about the bright, green top notes: refrigerate and make smaller batches.

Vinegar-forward sauces

Vinegar-forward sauces tend to be very stable and forgiving. They can hold for a long time, but they can still lose aroma over months if stored warm or exposed to air.

Fermented sauces

Fermented sauces often have built-in stability from acidity and salt. They can also continue to evolve.

That evolution can be good (more integration) or annoying (more funk than you wanted). Refrigeration slows the changes so the sauce stays closer to the flavor you intended.

Fruit-forward or sweet sauces

Sugar is delicious, but it changes storage dynamics.

These sauces are more likely to:

- darken over time,

- lose bright fruit notes,

- or change texture.

Refrigeration is strongly recommended.

“Can I leave it on the table?”

Commercial sauces are often formulated and processed for room-temperature stability. Homemade sauces vary widely.

For serving at a meal, it’s usually fine to leave sauce out briefly. For storage, use a simple rule:

- If you made it at home and you’re not testing/processing: refrigerate.

- If it’s commercial and says it’s fine on the shelf: follow the label.

If you have guests, the easiest safe move is to keep the bottle in the fridge and bring it out for the meal.

Signs your sauce is past its prime (and when to toss)

Not every change is dangerous, but some changes should stop you.

Changes that are often “quality” issues

- Color fading (especially in green sauces)

- Aroma becoming flatter

- Separation (can be normal depending on ingredients)

These are signals to use the sauce sooner, not necessarily to panic.

Changes that should make you pause

- Visible mold

- Off odors (putrid, rotten, “garbage”)

- Unexpected fizzing or pressure in a sealed bottle

- Texture that becomes slimy in an unpleasant way

When in doubt, throw it out. Sauces are cheap; consequences aren’t.

Keep flavor alive (not just safety)

Even stable sauces can taste dull if mishandled.

Here’s the flavor-preservation triad:

Store cool and dark

Heat and light fade aromatics. If you care about aroma, don’t store your best sauces next to the stove.

Minimize oxygen exposure

Cap tightly. Don’t half-cap. Don’t store open bottles for weeks as if air will “help.” Hot sauce is not wine.

Avoid dirty contact

Pour onto food. Don’t dip a used spoon or a bitten chip into the bottle.

If you’re gifting homemade sauce

Gifting sauce is fun, but it adds responsibility.

If you’re not testing and not processing for shelf stability:

- Gift it refrigerated.

- Label “keep refrigerated.”

- Include the date.

This is the simplest way to be generous without being careless.

pH testing (a practical middle ground)

If you’re serious about consistent results, pH testing is one of the highest-leverage upgrades you can make.

You don’t need to become a lab. You need enough measurement to stop guessing.

Two practical options:

pH strips

Strips are inexpensive and simple. They’re not perfectly precise, but they’re good for answering the big question: “Am I clearly in the acidic zone or not?”

The trick with strips is to test sauce that’s well mixed and not extremely thick, and to follow the instructions for reading time.

A digital pH meter

A meter can be more precise, but it requires calibration and care. If you use a meter, treat calibration as part of cooking, not an optional extra.

Either way, measurement doesn’t replace good handling. It just removes one major unknown.

Separation, sediment, and color changes (what’s normal)

Not every “weird-looking” sauce is unsafe. A lot of hot sauce is a suspension of solids in liquid, and suspensions separate.

Common normal changes

- Separation: watery layer on top, solids on bottom. Shake before using.

- Sediment: fine pepper particles settling over time.

- Color shift: green sauces turning more olive; bright reds darkening slightly.

These are often quality signals (freshness fading) rather than danger signals.

Changes that deserve caution

- Gas pressure: bottles that hiss, bulge, or fizz unexpectedly.

- Active bubbling when the sauce shouldn’t be fermenting.

- Slimy texture that wasn’t present before (especially if paired with off odor).

If you see those, don’t try to “save” the bottle by boiling it. When in doubt, discard.

A realistic room-temperature rule

People want a simple answer: “Can I keep this on the counter?”

Here’s a realistic rule set:

- Commercial sauces: follow the label.

- Homemade sauce without testing/processing: refrigerate.

- Fermented sauces: can be resilient, but refrigerate unless you are confidently measuring and processing for shelf stability.

This is conservative on purpose. It reduces risk and keeps flavor brighter.

Small handling habits that prevent most problems

If you want your sauce to stay good, these habits are more important than exotic ingredients:

- Use clean pour spouts or clean spoons each time.

- Wipe bottle necks so dried residue doesn’t become a contamination zone.

- Don’t cross-contaminate by dipping food into the bottle.

- Keep caps tight and store bottles upright to minimize leaks and air exchange.

You can make incredible sauce without being obsessive. You just need to be consistent.

Next steps

If you’re making sauce this week, use Making Hot Sauce for process, then explore the Hot Sauce Database to build a small shelf: one bright vinegar bottle, one smoky depth bottle, and one fermented tang bottle.

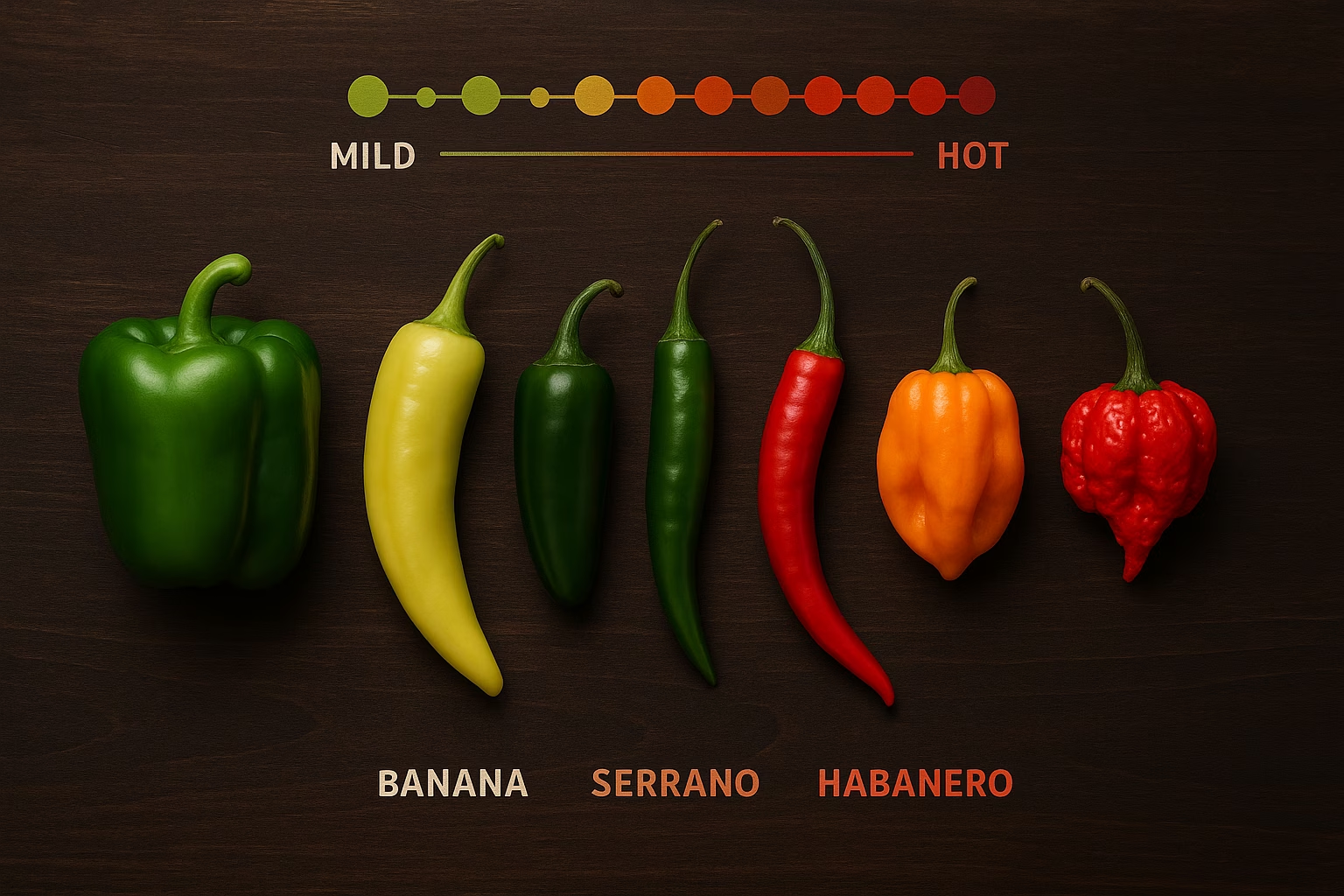

If you’re calibrating heat expectations, connect this with Understanding the Scoville Scale.